- Home

- »

- Tonguing

Tonguing

Detache

Staccato

Sostenuto

Accents

Legato tonguing

Double tongue

Triple tongue

Cutting the sound

Slured

Tonguing is achieved by “placing” then “removing” the tip of the tongue against the lips and upper teeth (as if pronouncing the sound “t” into the instrument).

Each note is allowed to resonate after the attack; the air is not cut off with the tongue at the end of a note (one pronounces “ta”, not “tat”: see Cutting the sound).

As with other instruments, there are several types of tonguing that horn players use depending on the style, origin, or period of the pieces being performed. For example, German tonguing tends to be longer, more sustained, and generous. French or Italian tonguing, on the other hand, is usually clearer and more airy.

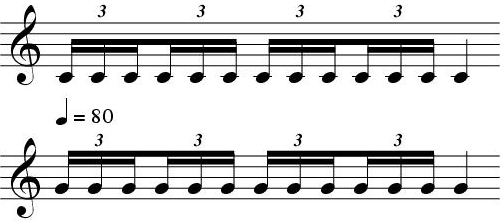

The speed of tonguing varies depending on each player’s abilities, but it cannot reach the same level as that achievable by flutists or clarinetists, for example. It is advisable not to write faster than sixteenth notes at a tempo of quarter note = 100–110. Higher speeds can nevertheless be reached using the double tonguing or triple tonguing techniques.

The maximum speed of tonguing also depends on the register. Since tone production is slower in the low register than in the high one, this maximum speed will be lower in the low register (even more so in the sub-low register).

The faster the air is pushed after the tongue is “removed” from the lips and teeth, the harder the attack will be, and vice versa (it is therefore very difficult to attack a loud note delicately and a soft note forcefully).

The staccato is a short tonguing. Just like with regular tonguing, its length depends on the style, the period, and the origin of the composer. The staccato symbol can be interpreted differently depending on the context: as a simple detache (for example, in Brahms’ works), or as a more pronounced staccato (especially in French or Italian music). In contemporary music, horn players are more likely to treat this notation as a separated staccato, contrasting with regular detache tonguing.

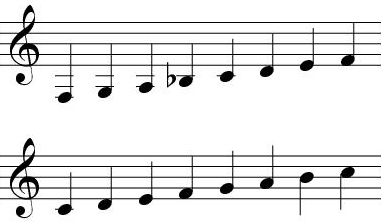

The staccato symbol can also be used to specify or confirm a separated articulation in a group of fast notes. For example, the articulation “two slured notes, two tongued notes” (which helps to smooth out groups of four sixteenth notes) can be written with two tied notes and two staccato notes (though this is not always the case).

Short notes are feasible across the entire range of the instrument. However, it should be noted that for the extreme low register and for long fingerings (see Generalities – Table of harmonics and fingerings – Fingerings intonation), the vibration of the lips is slower, making it more difficult to play short (even more when the tempo is fast). However, this is still entirely achievable by professional musicians.

The sostenuto tonguing is a long and sustained articulation. It may indicate that the note to which it is attached should be held continuously until the next note, or that the note is significant and should be emphasized. If several consecutive notes are marked with loué, this can also give a stronger sense of direction to the group of notes. All of this depends on interpretation and context, and does not need to be specified—unless necessary.

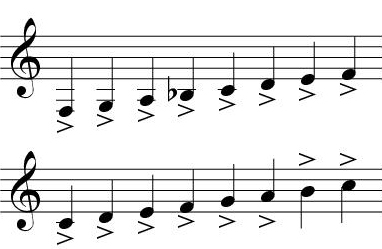

Accents indicate a marked articulation, emphasizing the note to which they are attached. Often used in loud dynamics or tutti passages for added power, they can also appear in softer dynamics to slightly reinforce the attack of a note.

To produce an accent, one should simply begin the note with greater air speed and air volume than usual. The more these two elements are increased, the stronger and more pronounced the accent will be, and vice versa.

Other factors influence how notes are accented, and these are represented by different notations:

The marcato wedge accent is even more marked than the regular accent. Its main characteristic is a stronger and more incisive attack.

The keil is an incisive, short, and bouncing accent. It combines elements of the staccato, the accent, and the wedge, but the note it is attached to still maintains a forward motion. It is not a vertical accent.

Sometimes, accents are not marked as articulations, but rather as dynamics:

The fortepiano is performed by shifting from a strong to a soft dynamic, but without a real accent. The forte part lasts longer than in a regular accent, in order to clearly distinguish it.

The forzando indicates that the note it is attached to should be brassy or played forcefully within a soft dynamic.

The sforzando is an expressive accent (widely used in Romantic music) whose execution relies on the air speed. The resulting effect is like a quick crescendo–decrescendo that reinforces an important note.

The sforzato is a blend of the two previous dynamics. It is very powerful and brassy, but remains horizontal rather than vertical.

It is also possible to combine tonguing and slurring by separating the notes very briefly while maintaining continuous airflow. This is known as “legato tonguing”.

A good image for executing this articulation is that of a stream of water from a tap, into which one quickly passes a finger at a steady tempo—the stream representing the air, and the finger interrupting it representing the tongue.

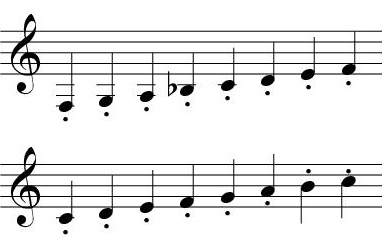

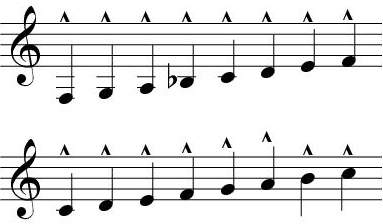

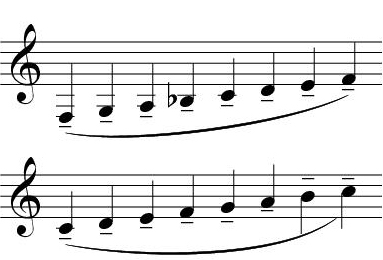

This articulation can be written in various ways:

It is a tongue legato closer to the detache than to the legato. There is a real attack (pronounced either “t” or “d”) on each note and a lot of decay. The tone remains continuous. The “legato tonguing” character is given by a stronger direction in the group of notes compared to the detache articulation.

It is a tongue legato closer to the legato than to the detache. There is a softer attack (pronounced “d” or even “l”, rather than “t”) on each note. The sound and the air are very continuous. The “legato tonguing” character is given by a stronger direction of the group of notes compared to the sostenuto.

It is a legato with “diaphragm accents”. By sending a larger amount of air and pressure all at once, the sound “swells” suddenly and briefly.

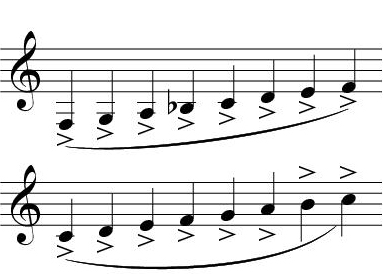

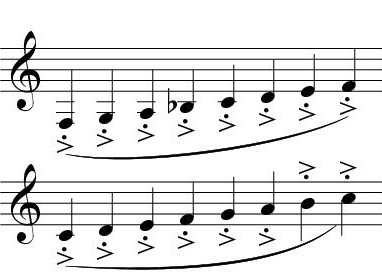

The legato tonguing can be expressed in various forms and combinations of articulations, of which the most common are listed below. Be careful, if you want to achieve a very specific articulation through these notations, make sure to specify it in the notice (since the way these articulations are interpreted is not completely established, it can vary depending on the musicians).

One can make “normal” accents (separated), but with more direction and a slightly more continuous sound than in detache, similar to the slur with dots. To really specify this articulation, you can then layer accents, dots and slur.

One can make longer accents, with direction and a very continuous sound, similar to the slur with dashes. To really specify this articulation, you can then layer accents, dashes and slur.

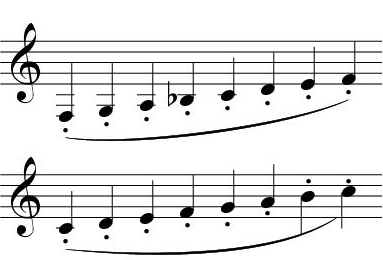

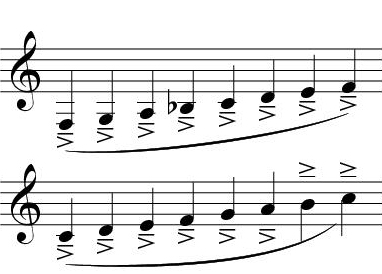

In a group of tongued notes, the faster the required speed, the harder it becomes to pronounce “t t t t”, so we alternate between “t” and “k”. To pronounce these two consonants, the tongue must be placed in different areas of the mouth and the palate, it is then possible to alternate between these two positions, which is much faster than repeating the same position.

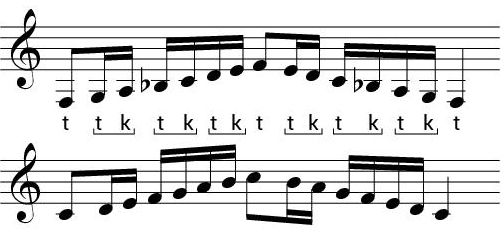

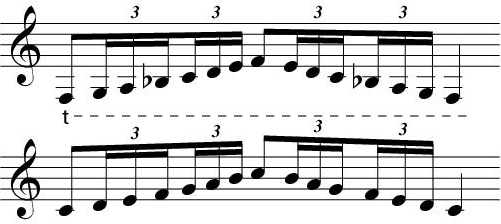

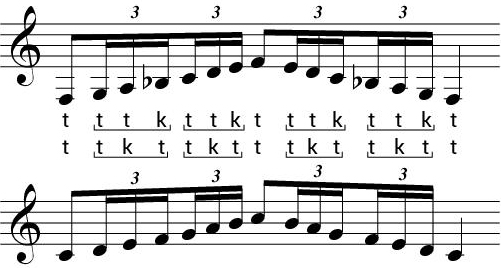

Thus, to perform fast binary rhythms, one will pronounce “t k t k”: this is the double tonguing. Similarly, to perform ternary rhythms, one will pronounce “t k t” (generally preferred by woodwinds) or “t t k” (generally preferred by brass): this is the triple tonguing.

The consonant “t” being harder than the consonant “k”, attacks with “t” will be slightly more defined and stronger than those with “k”, although the aim of practicing double and triple tonguing is to smooth out the differences in sound between these consonants. However, the faster the tonguing, the less the difference between the “t” and “k” will be heard.

Due to these differences in vowel definition, it is possible for a rhythm (almost imperceptible) to emerge from triple tonguing. For example, rhythms pronounced “t k t” will tend to have the “t” sounds emphasized, creating a long-short rhythm. Rhythms pronounced “t t k” will have more forward direction and will be more effective for upbeats, for example. However, these differences should not be specified (unless truly necessary) in the score, as it is up to the musician to choose the technique that seems most appropriate given the context, or the one they are most familiar with.

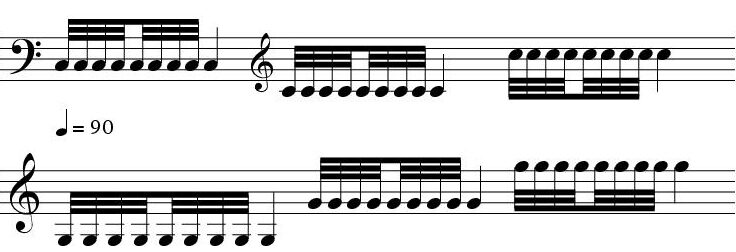

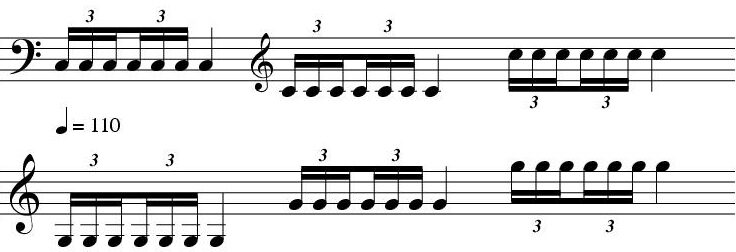

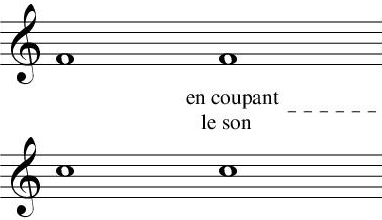

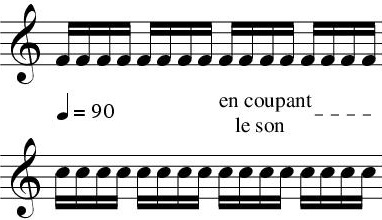

With these techniques, very high speeds can be reached (as fast as one can pronounce them out loud): roughly thirty-second-note at quarter note = 90 in double tonguing, and sixteenth-note triplets at quarter note = 90-110 in triple tonguing (a slightly lower speed, since looping “t k t” or “t t k” involves two consecutive “t” articulations, which are mechanically slower).

There is, however, a “pivot” tempo at which it becomes to fast to use single tonguing in a confortable way, while for double or triple tonguing it isn’t yet quite fast enough (in this case, the difference between the “t” and the “k” becomes too noticeable). This tempo varies depending on the player’s ability, but generally lies between sixteenth notes at quarter note = 120 and quarter note = 150. It is therefore advisable, when possible, to avoid writing tongued passages for horn within this speed range.

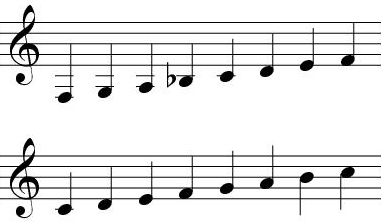

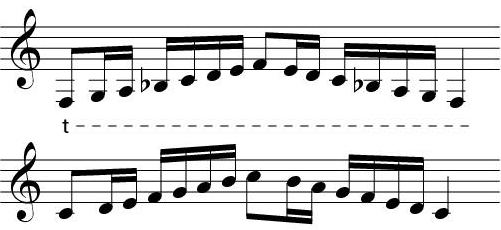

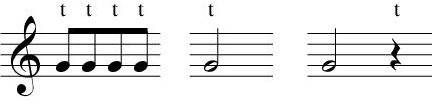

Note: these two cells are played once using single tonguing and once using double/triple tonguing

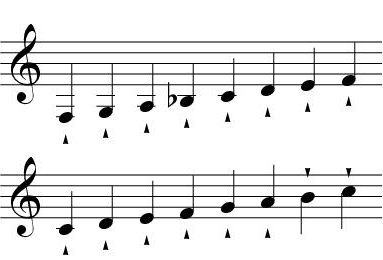

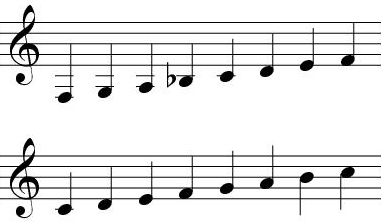

Cutting the airflow with the tongue is possible on all brass instruments to achieve a specific effect—for example, to imitate electronic sounds with a very sharp and defined start and end. In this case, one pronounces “t” both at the beginning and at the end of the note, resulting in a dry, abrupt cutoff with no resonance. However, classical technique generally avoids this as much as possible, favoring resonant notes instead.

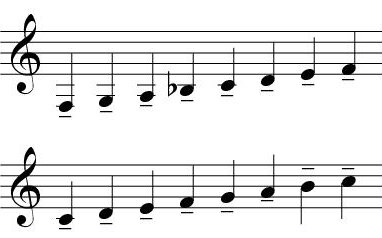

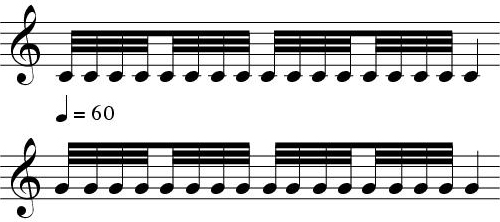

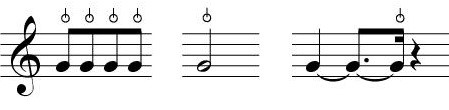

Played with normal tonguing

Played while cutting the sound with the tongue

This effect can be used at the end of a sustained note or at the end of a short note. However, in the latter case, care must be taken that the tempo is not too fast, so there is enough time to pronounce the final “t” (no faster than sixteenth notes at quarter note = 90).

There is currently no established notation for this effect. The composer is therefore free to choose the symbol that best represents it (in which case it should be clearly explained in the notice or as a footnote). Certain symbols should be avoided because they refer to other techniques—for example, the one used for damping a string on the harp is very similar to the symbol for half-stopping. Here are several possible symbol ideas:

The most intuitive and clear option for a horn player would be to write a “t” above the moment or location where the note should be cut off. It would therefore be placed directly above the note to indicate a very short note, or above the rest following the note (or slightly before) to show that it should be cut off at the end of its value (much like consonants at the end of the words for singers).

It is also possible to use the staccato dot symbol, repurposing its function. In this case, its effect would no longer be to shorten the note, but rather to give it a clean, precise ending.

The Bartók pizzicato symbol can also be used, as it clearly indicates the short, abrupt nature of this technique. However, it may still be ambiguous: it suggests something percussive, whereas this technique is not.

Finally, it is also possible to place a symbol on the stem or head of the note that should be cut off.

Be sure, however, to clearly explain the chosen notation in the notice or in a footnote, in order to avoid ambiguity, confusion with another symbol, or misinterpretation (particularly regarding the notation involving the staccato dot symbol).