- Home

- »

- Microtonality

Microtonality

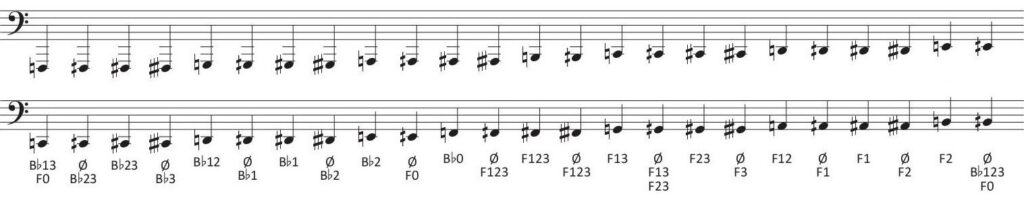

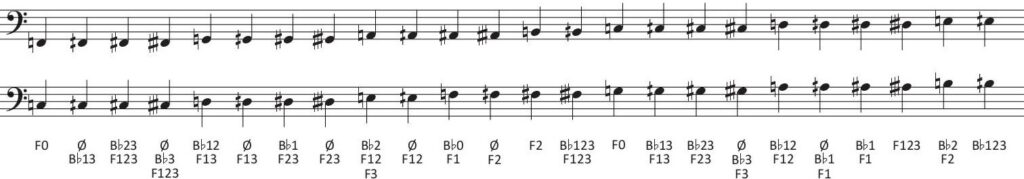

Heard in C:

Written in F:

In C

In F

In C:

In F:

In C:

In F:

In C:

In F:

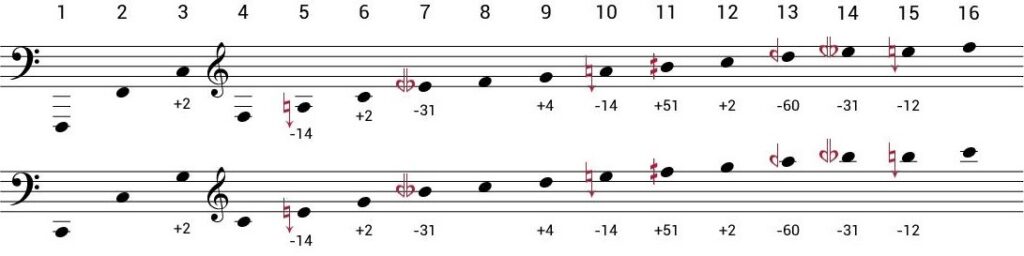

Micro-intervals can be achieved on the horn in several ways. The most accessible and straightforward method, chosen by most horn players, is to lower the intonation of each note by slightly bending the hand further into the bell, or to raise it by pulling the hand out of the bell.

The advantage of this technique is that it does not require any special learning or thought process, as it simply involves playing the nearest higher “in-tune” note while covering the bell more or less. For this reason, it is more visual, intuitive, and practical to notate micro-intervals using “fractions of a flat” rather than “fractions of a sharp.” Unfortunately, this technique is not very precise because there are few or no clear reference points to remember the exact hand adjustment for each encountered micro-interval. Moreover, due to the hand being inserted further into the bell, the sound is more or less altered (the further the microtonal note is from the tempered note, the more the bell must be covered, and the more muffled the sound will become). Finally, the margin for adjusting intonation with the hand is not consistent across the horn’s full range: the higher the register, the smaller the margin becomes. It also depends on several other factors, including the instrument used and the horn player themselves.

The second method, which is more complex but also more stable, involves using the naturally high or low intonation of the harmonic series compared to a tempered chromatic scale. In the harmonic series shown below, the 5th harmonic is slightly flat, the 6th harmonic slightly sharp, the 7th is even three-quarters of a tone too flat, and so on.

Theoretically, one could even indicate the number of commas of difference between these harmonics (see above). In practice, however, each instrument (even from the same maker and of the same model) is different, and the placement of the harmonics remains quite variable. Following the same logic, the harmonic series of different fingerings can also vary significantly. Adding to this the fact that it is possible to modify a note’s intonation quite substantially using only the lips (see Intonation), it becomes clear that achieving perfect comma-level tuning of a microtonal note is almost impossible to execute in a stable and consistent way.

Relatively precise and stable fingerings will therefore be used for each microtonal note, causing little to no alteration of the sound. However, using this technique does not guarantee a completely homogeneous tone, as it often requires switching between the F horn and the B♭ horn, which do not have exactly the same timbre (see Usual Techniques – Sound color in F or in B♭). It also demands learning more fingerings and mastering them, or referring to a fingering chart (see the Quarter-tone fingering chart at the beginning of the page).

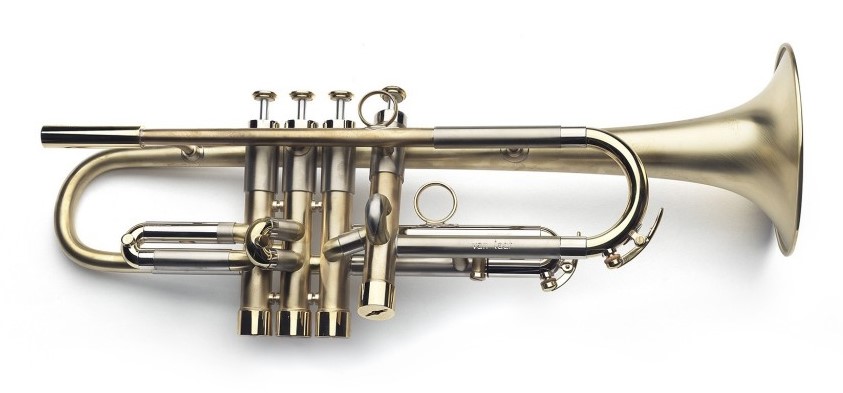

Finally, attempts have been made to design and build horns with an additional valve allowing the tubing to be lengthened by a quarter tone (or even another fraction of a tone), similar to Ibrahim Maalouf’s quarter-tone trumpet. This is the case with the Samuel Stoll’s horn, built by Marc Schmiedhäuser (a maker based in Wiesbaden, Germany). On this instrument, just like with the hand technique for producing quarter tones, each note is played using the fingering of the next higher tempered note while pressing the quarter-tone valve. This is the only way to make quarter tones sound exactly like tempered notes.

“Quartertone” trumpet used by Ibrahim Maalouf

Unfortunately, these horns have not yet become widespread, and very few horn players own one (even among those specialized in contemporary music). This may be due to the difficulty for makers to build instruments that are both homogeneous and well-calibrated for the tempered part of the horn as well as the microtonal one. It might therefore be worthwhile to encourage these developments in instrument making by continuing to write microtonal music for the horn.

In the meantime, it is still possible to adjust the main tuning slide of the horn by pulling it out or pushing it in to raise or lower the overall length of the instrument by up to an eighth of a tone. However, this of course depends on the horn model being used, as some have longer slides than others. Schmid horns, for example, often feature a double main tuning slide allowing the instrument to be lowered to E and then to E♭, and can be pulled out as much as needed to achieve all micro-intervals. However, in this case, tempered notes are also affected, since this adjustment lowers the intonation of the entire instrument rather than just specific notes.