- Home

- »

- Range and registers

Range and registers

Horn transposition

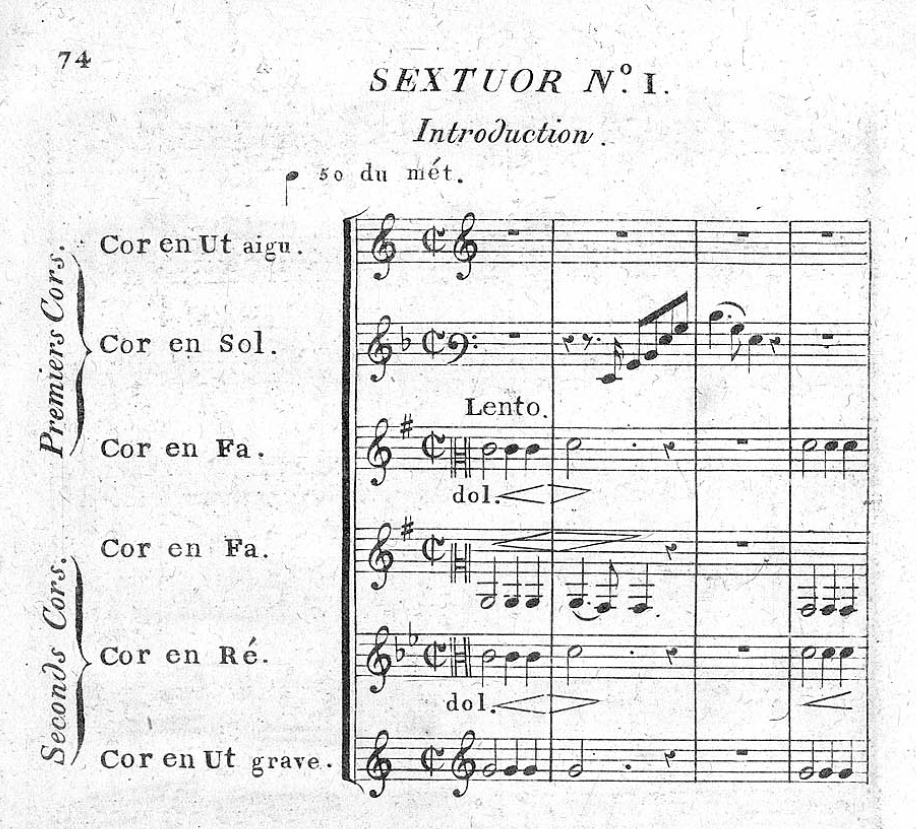

When looking at horn parts written before the second half of the 20th century (the same applies to trumpet parts), one notices that the horn is written in many different keys, ranging from low B♭ to high C. This is due to the long-standing tradition of writing for the natural horn, which remained unchanged for a long time. Indeed, before the Romantic era, horns were very different from those we know today (see Generalities – The different types of horns – Natural horn); they had no valves but instead used crooks to change the key of the instrument. Depending on the crook used, the horn could be in F, D, A, and so on. Horn parts were then written using the natural harmonics of the key that corresponded to the piece’s key (or that of the dominant), which meant that the horn player was essentially always reading in C major. This is also why key signatures were not written on horn parts.

Horn distribution in Louis-François Dauprat’s First Sextet

Despite the improvements in instrument making and the advent of valves, this tradition of notation remained, probably because it is the way horn parts sound best. It was only during the 20th century that the horn began to be treated like other instruments in terms of notation, and started being written in F with a key signature.

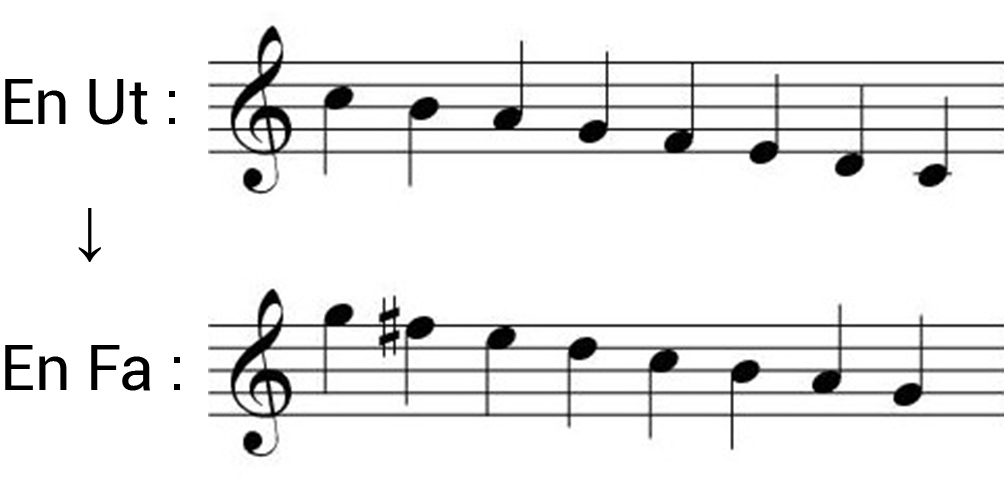

The horn is therefore a transposing instrument in F, which means that a note written in C must be transposed up a perfect fifth to produce the pitch played by the horn player. Conversely, a note written in F must be transposed down a perfect fifth to match the pitch heard in C. This applies regardless of the clef used (treble or bass clef; see The clefs).

The range

Generally speaking, most horn players agree that the range of the horn spans four full octaves. This range can be extended, but it should be used with great caution, as most horn players will not appreciate it.

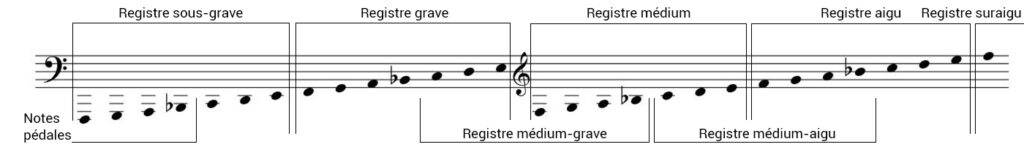

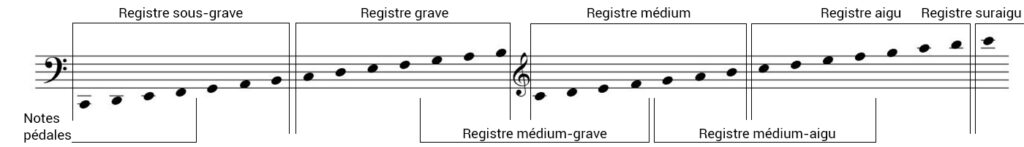

On this website, I often refer to registers that correspond to different pivot notes of the horn’s range (these boundaries are of course approximate and depend on each horn player):

The medium register is the first one mastered when learning the horn. However, in solo repertoire, this register is often overlooked because it may not be as powerful or agile. It is the register most suited for fulfilling, accompaniment and sustained roles. Indeed, its rich and warm sound blends very well with the orchestra or other instruments.

The medium-high register is the register best mastered by most horn players. It is the most comfortable of all and provides the widest range of tonal colors in the horn’s range. It is also the register traditionally favored for solo works.

The high register is the typical brilliant solo register. It can be played with great agility as well as with great power, and it can be very resonant. However, it remains quite difficult to master and requires good control.

In the extreme high register, the harmonics are very close together and standard fingerings are highly inaccurate, making it easy to miss a note. Furthermore, this register requires a lot of energy, which is very tiring for the lips as well as for the abdominal muscles needed to provide the necessary air pressure. As a result, it is essential to exercise great caution (with significant rest time before, during, and after a high passage—especially if it is long and loud—and with relatively easy material before and after to allow recovery) before using this register, and to make sure the transition into these high notes is well prepared. Large leaps in tessitura should be avoided as much as possible, as both the lips and breath need to be ready for such efforts. These passages should be limited to a few appearances within a piece, and by no means used throughout its entirety.

The medium-low register is the appropriate register for low horns. It allows for a noble and broad sound, though it is not easily suited to virtuosity. On the other hand, it is the least comfortable register for most high horn players, as this is typically where they need to change their lip position to reach the low register comfortably. Some horn players switch to the F horn starting from the top of this register and continuing down to the lowest notes. This approach allows for an even more captivating sound in the low range of the instrument, but it can also unbalance the sound of the horn section if the other hornists play on the B♭ horn.

The low register is traditionally used to play the bass lines of chords in the orchestra or to double octaves with the other horns. Since sound production in this register is slower than in the higher registers, it is more difficult to articulate quickly, which is why it is generally reserved for low horns.

The extreme low register contains the pedal notes—that is, the fundamental harmonics of the B♭ horn (those of the F horn lie even lower). These notes can be very brassy and bright if played with enough energy and at a strong dynamic. However, they won’t speak as clearly as on a trombone, due to the backward-facing bell. However, the lowest notes in this register are too deep to give this effect and have too little volume to be used in tutti passages. They will only be effective in small instrumental ensembles or in very sparse orchestrations; otherwise, they won’t be heard.

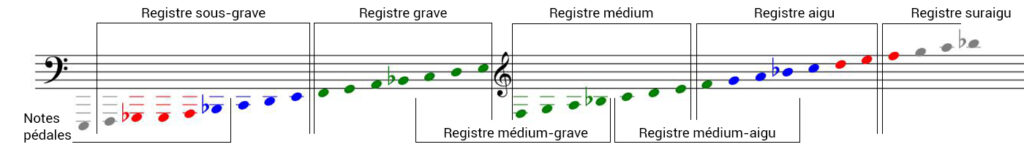

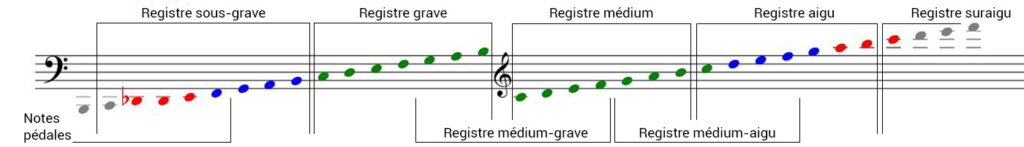

Here is a representation of the difficulty of execution and sound production across each of these registers. The very easy range is shown in green, the usual range in blue, the difficult range in red, and finally, in grey, some extreme notes that are almost never required and that some horn players cannot reach. Of course, this representation should be interpreted with nuance, depending on each player’s individual abilities and limitations.

The clefs

The horn is written in treble clef. The bass clef is very rare and is only used during a long passage often descending below the B♭ in the middle of the bass clef in C (low F in F).

In this range, isolated notes are always written in treble clef. It is only from the low F of the bass clef in C (low C in F) that isolated notes should be written in bass clef.

There is no need to be afraid of adding extra lines below the treble clef staff, as horn players are used to it. However, (apart from low horn parts in horn or brass ensembles, and even then…) it is better to avoid adding extra lines above the bass clef staff.

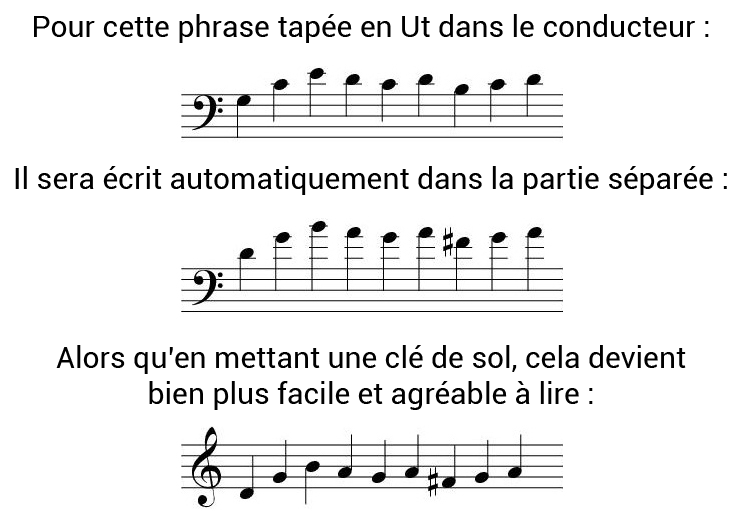

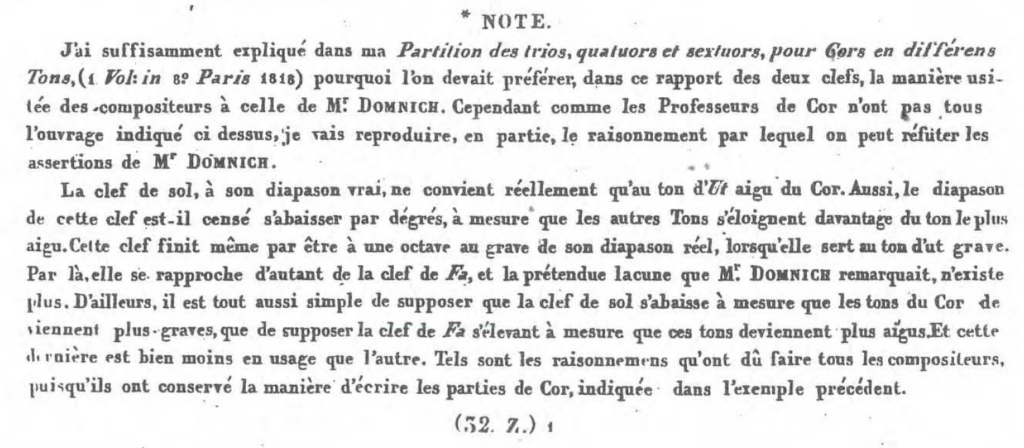

Traditionally, a note in the bass clef was written a fourth below the note heard in C (an octave lower than the pitch at which it should be written according to the modern way). This allowed for a better representation of the lower register, which sounded closer to this notation than to the current one. Louis-François Dauprat (1781-1868) also explains very well the advantages of this notation in Article 14 (page 22) of his Méthode de Cor-Alto et Cor-Basse:

Louis-François Dauprat explaining the advantages of the old bass clef notation compared to the new notation, as introduced by Heinrich Domnich.

Louis-François Dauprat, Méthode de Cor-Alto et Cor-Basse (1824), Article 14 page 22

Now that lower notes can be played, this notation becomes problematic as it requires adding many extra lines below the bass clef. It also differs from the way we learn music theory. The modern bass clef notation (where a note in the bass clef is written a perfect fifth above the note heard in C) is therefore now accepted and predominantly used.

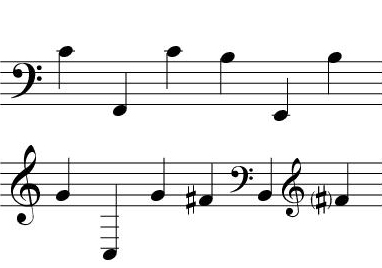

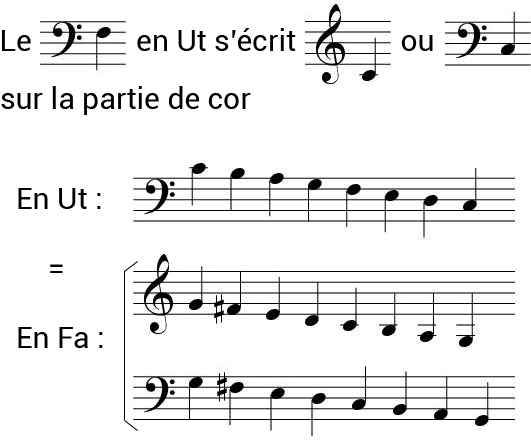

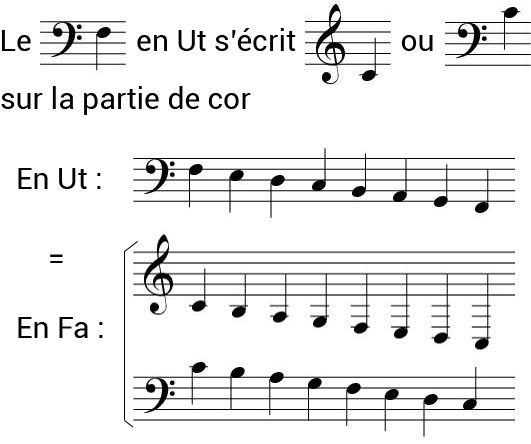

Old notation :

Modern notation :

However, the old notation still persists, which is why it’s important to specify in the notice the transposition of the bass clef being used (especially if there is no note with multiple extra lines below the bass clef that could clarify the issue).

In this excerpt from the 4th horn part of Variation VII of Don Quixote by Richard Strauss, there is no ambiguity; it is the old notation.

Indeed, the notes below the staff would completely fall outside the instrument’s range if it were the new notation.