- Home

- »

- Glissandi

Glissandi

Harmonic sweep

All valves pressed

Moving the valves

Hand bending

Half-valve

With the mouthpiece partially pulled out

Mouthpiece only

-

Harmonic sweep

-

All valves pressed

-

Moving the valves

-

Hand bending

-

Half-valve

-

With the mouthpiece partially pulled out

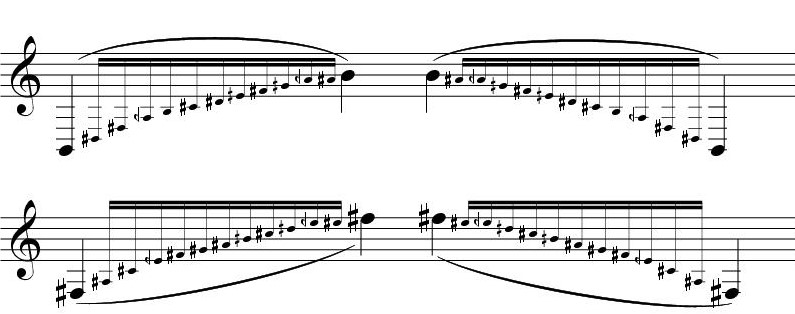

Since the natural harmonics are very close together on the horn, performers will instinctively tend to use harmonic sweeping to produce a glissando. This technique does not create a continuous glissando, as it involves jumping from one pitch in the harmonic series to another. As a result, one can often perceive a harmony—that of the harmonic series based on the fundamental being used (see Table of harmonics and fingerings).

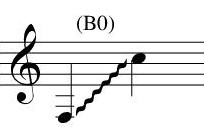

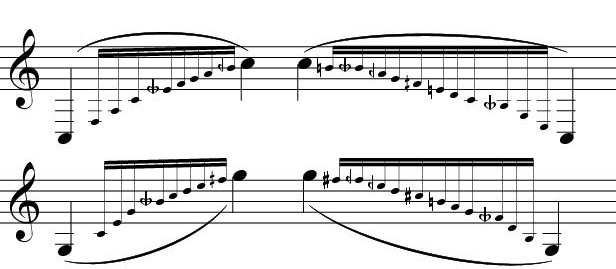

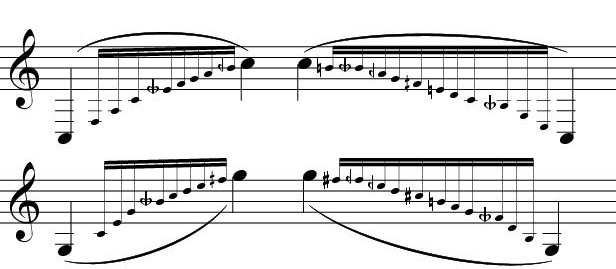

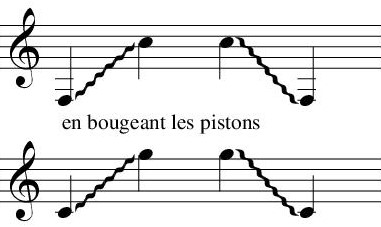

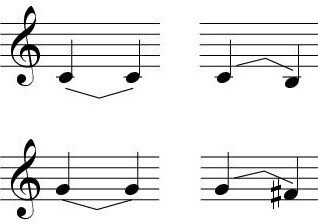

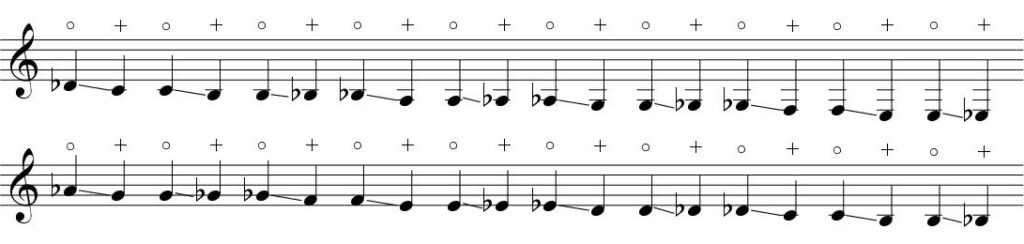

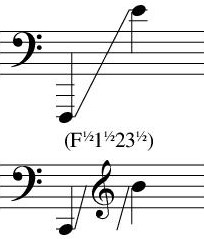

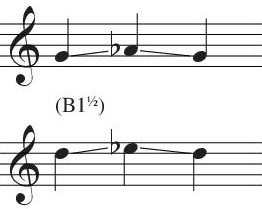

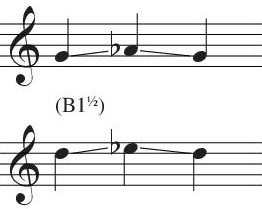

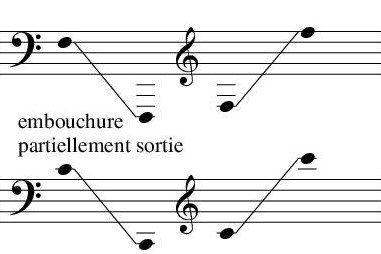

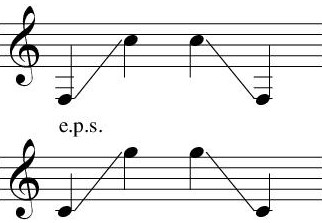

It is notated by writing all the pitches touched during the glissando in small notes, or at least the main ones (this is the most common notation):

It can also be notated more simply by indicating the fingering of the desired harmonic series:

It is notated by writing all the pitches touched during the glissando in small notes, or at least the main ones (this is the most common notation):

It can also be notated more simply by indicating the fingering of the desired harmonic series:

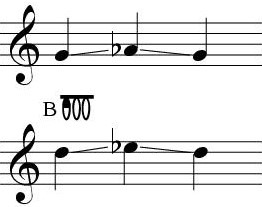

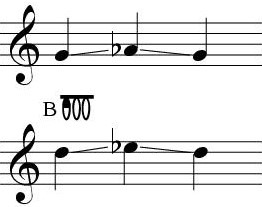

The glissando with all valves pressed down corresponds to a harmonic sweep on the B natural (in C) harmonic series. Pressing all the valves creates the longest possible tubing on the instrument, producing the lowest fundamental and making the harmonics the most closely spaced. As a result, this harmonic sweep is the most “continuous” (allowing the player to touch the largest number of notes) of all harmonic sweeps.

It is of course possible (and in fact this is the most common way this type of glissando is used) to start a glissando on any note, regardless of fingering, then press all the valves during the slide, and end on any other note.

It should be noted that the longer the tubing, the less in tune the harmonic series becomes. The slides are not designed to be used all together: when it is the case, the instrument’s body is slightly too short for the harmonic series to be accurate, resulting in intonation that is approximately a quarter tone sharp.

Finally, since this is the maximum possible tubing length, the sound tends to be more easily brassy even at moderate dynamics and may lack projection.

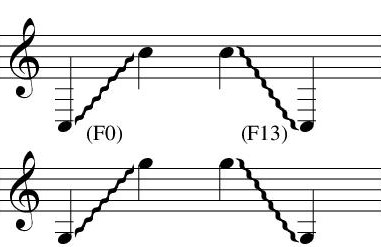

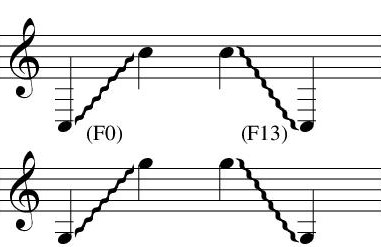

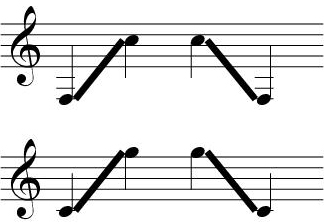

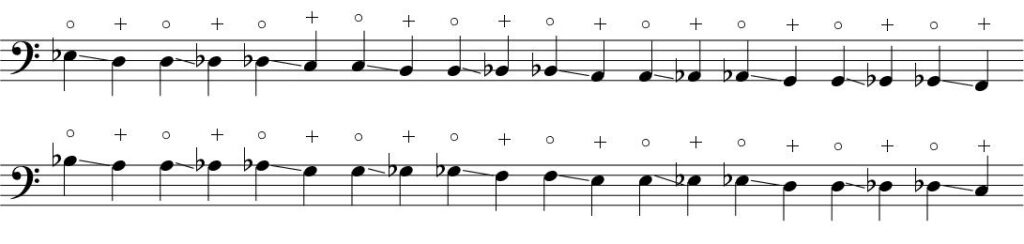

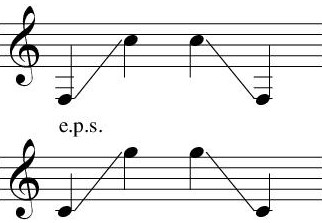

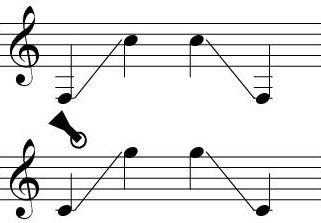

It can be written out in full, as in the previous examples—in which case there is no need to specify the intended effect, since the notation speaks for itself. If a more visual symbol is needed, a thick glissando line can be used (see opposite), but in that case its meaning must be clearly explained in the notice or as a footnote.

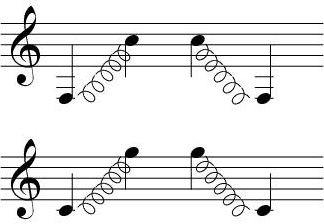

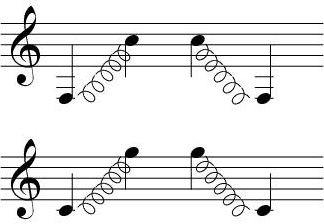

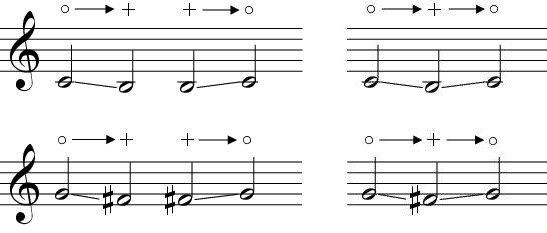

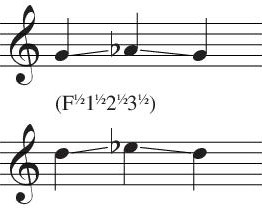

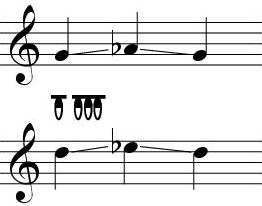

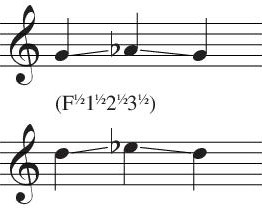

By rapidly and alternately pressing each valve, one can produce a glissando that is more granular than the harmonic sweep. This is the most homogeneous glissando technique across the entire range, as it allows for filling in the notes usually missing in the low and extreme-low registers when using harmonic sweeping. It is also more precise than the latter, due to the possibility of changing fingering on the target note.

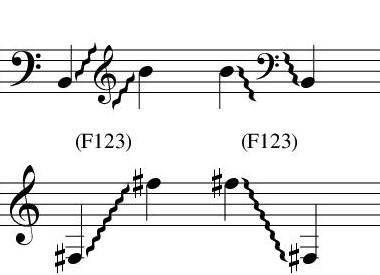

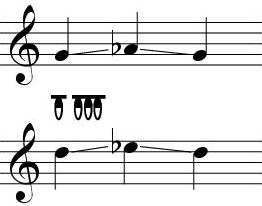

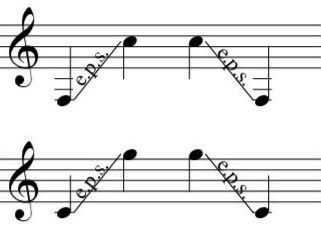

There is currently no established notation for this effect. The simplest and most effective way to indicate it would be to write out “moving the valves” in full (possibly as a footnote). If a symbol is needed, an intuitive one for the horn player would be the one shown here (provided, of course, that its meaning is clearly explained in the notice or in a footnote).

There is currently no established notation for this effect. The simplest and most effective way to indicate it would be to write out “moving the valves” in full (possibly as a footnote). If a symbol is needed, an intuitive one for the horn player would be the one shown here (provided, of course, that its meaning is clearly explained in the notice or in a footnote).

Glissandi are also possible by gradually covering the bell with the hand. Due to the curvature of the hand, the tube lengthens progressively, and the pitch lowers by approximately a half-step (slightly less in the extreme-low and in the high registers). This physical phenomenon is actually what is exploited in the natural horn technique to produce all the degrees of the chromatic scale. It is also for this reason that the horn player must transpose when playing stopped or covered notes.

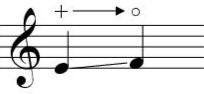

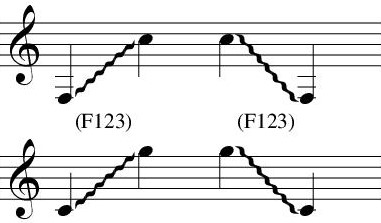

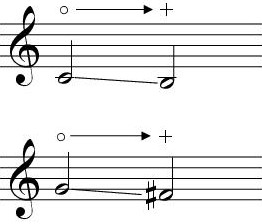

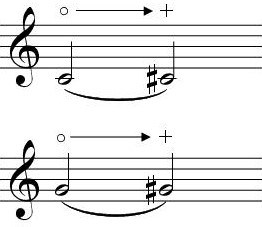

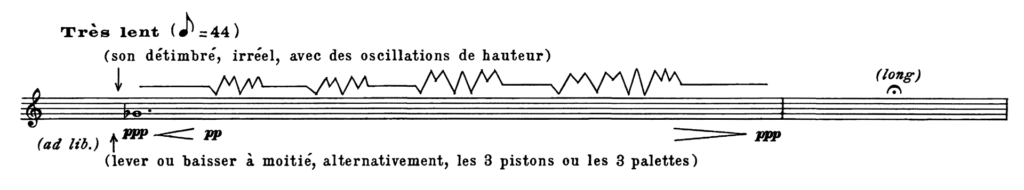

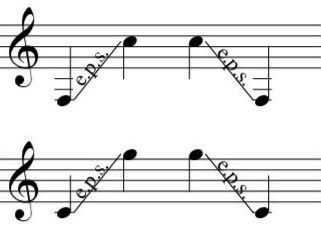

Since this is a progressive glissando, it can be written with a continuous line to differentiate it from granulated glissandi, where several notes can be heard within the glissando. To specify that it should be performed with the hand, simply place a small circle (signifying open playing mode) on the highest note of the glissando, and a small cross (signifying stopped playing mode) on the lowest note of the glissando. Optionally, an arrow can be placed between these two signs to specify the transition, though this is not mandatory.

Note that the sound produced will not be a brassy stopped sound, but rather a soft covered sound. The reason for writing it with the stopped note sign is simply out of habit and ease. It is entirely possible to write it with a cross inside a circle (signifying covered playing mode) if that makes more sense, and it will be understood and interpreted in the same way (unless otherwise specified in the notice or in a footnote).

The previous notation is the clearest for horn players. However, here is another suggestion that could be useful, especially in the context of a pitch bend (either downward or upward), and which might provide a better representation of the desired effect (of course, to be explained in the notice).

It is also important to consider the change in sound intensity when transitioning to covered or stopped sounds while executing this effect. The sound will become slightly quieter during a descending glissando (since it moves from an open sound to a stopped sound), and conversely, the sound will become slightly louder during an ascending glissando (since it moves from a stopped sound to an open sound). This can though be avoided by playing a bit more the covered note.

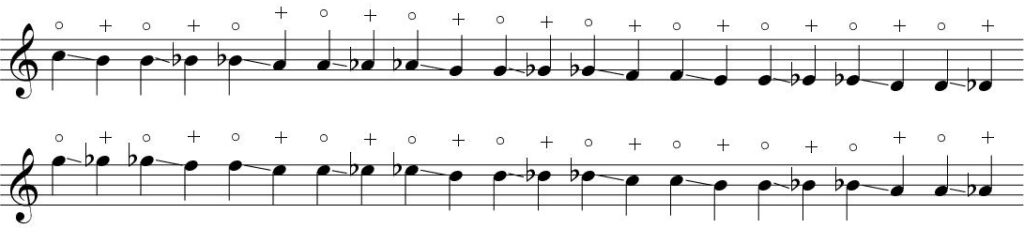

This type of glissando is only possible over semitone intervals, and therefore cannot be used across the full range of the instrument. However, by placing several glissandi side by side, it is possible to cover a significant range—though it is very difficult to precisely synchronize the transition from the stopped end of one glissando to the open beginning of the next on the same note (see example below).

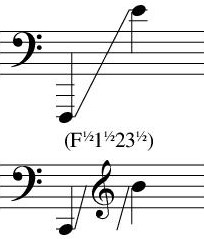

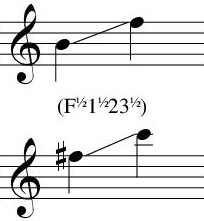

The higher or lower the register, the smaller the interval over which this effect can be achieved (a semitone, then a quarter tone, an eighth of a tone, until no pitch change can be heard—see the wah-wah effect). It is therefore best to use this effect within the following interval:

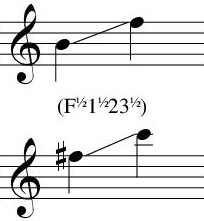

By half-pressing one or more valves, the air flows simultaneously through the main tubing (as when the valve is unpressed) and through the corresponding valve slide, creating interference. This interference makes the sound much more flexible, allowing for glissandi. Unlike those produced by harmonic sweeps or valve changes, this is a continuous glissando. However, it remains continuous only over short intervals.

Moreover, the range over which a glissando is possible depends on which half-valve is used. It is therefore possible to switch fingerings (at the right moment) to achieve a near-continuous glissando across the full range. The more valves are half-pressed, the greater the interval over which a glissando is possible—but the more altered and less audible the sound becomes. Conversely, using fewer half-valves results in a clearer sound but a smaller glissando interval. As a result, a glissando involving three or four half-valves at once will not have a completely even dynamic level.

Because of the interference, the sound is completely altered and no longer resembles that of a natural horn tone. This should be taken into account if one intends to write this type of glissando between two normally played notes. The dynamic range of half-valve playing is also very limited—it is not possible to play softer than piano, nor louder than mezzo-forte.

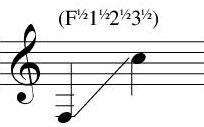

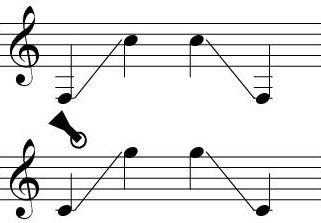

There is no established notation for this effect, so it can be written out in full as “half-valve”, and a broken line can be drawn following the inflections of the glissando (see Messiaen – Des canyons aux étoiles – Appel interstellaire).

Olivier Messiaen – Des Canyons aux étoiles – VI. Appel interstellaire – bar 14

The glissando line can simply be notated with the abbreviation “1/2” for “half-valve” placed along the glissando line. However, this notation should still be explained in the notice or in a footnote, as it is not standard.

Notating the desired fingering (see Extended techniques – Half-valve) can also be helpful, especially when a specific timbral change in the glissando is intended.

By partially removing the mouthpiece from the leadpipe and placing it at the entrance at a certain angle, not all of the air flows fully into the instrument. The resulting sounds are only a partial amplification—via the instrument—of the sounds produced by the mouthpiece itself, which do not have a clearly defined pitch. This makes it possible to slide continuously across the entire range of the instrument.

This technique, however, requires holding the instrument with one hand and the mouthpiece with the other, which means a brief pause is necessary to get into position and find the right angle between the mouthpiece and the leadpipe. It cannot be immediately followed by an ordinary playing technique.

A good example of this effect can be heard in the introduction played by Hervé Joulain, principal horn of the Orchestre National de France, in Gods and Wailings by the artist Cathialine. In the video clip, the hornist appears to be playing in a normal position, but he explained in a tweet how he actually created the effect in the studio.

Since this is a continuous glissando, it should be notated with a straight line. However, as there is currently no established notation for this effect, it is essential—regardless of the chosen notation—to explain it clearly either in the performance notes or in a footnote. The simplest approach is to write it out in full (as in the earlier example), or to use an abbreviation (such as “m.p.p.o.” for “mouthpiece partially pulled out”). A schematic or symbolic notation can also be used—for instance, the symbol proposed here represents the mouthpiece positioned at the edge of the leadpipe.

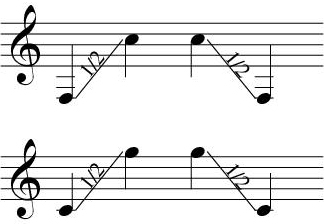

If it is necessary to distinguish between a grainy glissando (produced by harmonic sweeping or moving the valves) and a continuous glissando (hand bending or half-valve) within the same piece, the former can be notated with a wavy line and the latter with a straight line. However, since this is not standard notation, a clear explanation should be included in a footnote or the notice, detailing each technique and its corresponding symbol.